I am always on the lookout for simple explanations of what Community Benefit Agreements (CBAs) are and do. These definitions come in handy not only in my work but in my daily life when I have to answer the standard question, “What do you do?”1 One complicating factor is that the term Community Benefits has come to be used differently in different places. Here I want to consider a few definitions that struck me as representative.

The Community Benefits movement originated in the US about 25 years ago, with the Staples Centre in Los Angeles as the first major example of the concept in 2001. Jovanna Rosen, in her 2023 study, Community Benefits: Developers, Negotiations, and Accountability, outlines the history of the movement:

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, community advocates began to use their selective support for development projects, rather than resistance, to compel developers, labor unions, and local governments to meet at the negotiating table. Within a history of community exclusion and harm from urban development, community activists posed a simple but critically important question: Who would benefit from future local development? Communities sought to create tools to improve equity in the development process.2

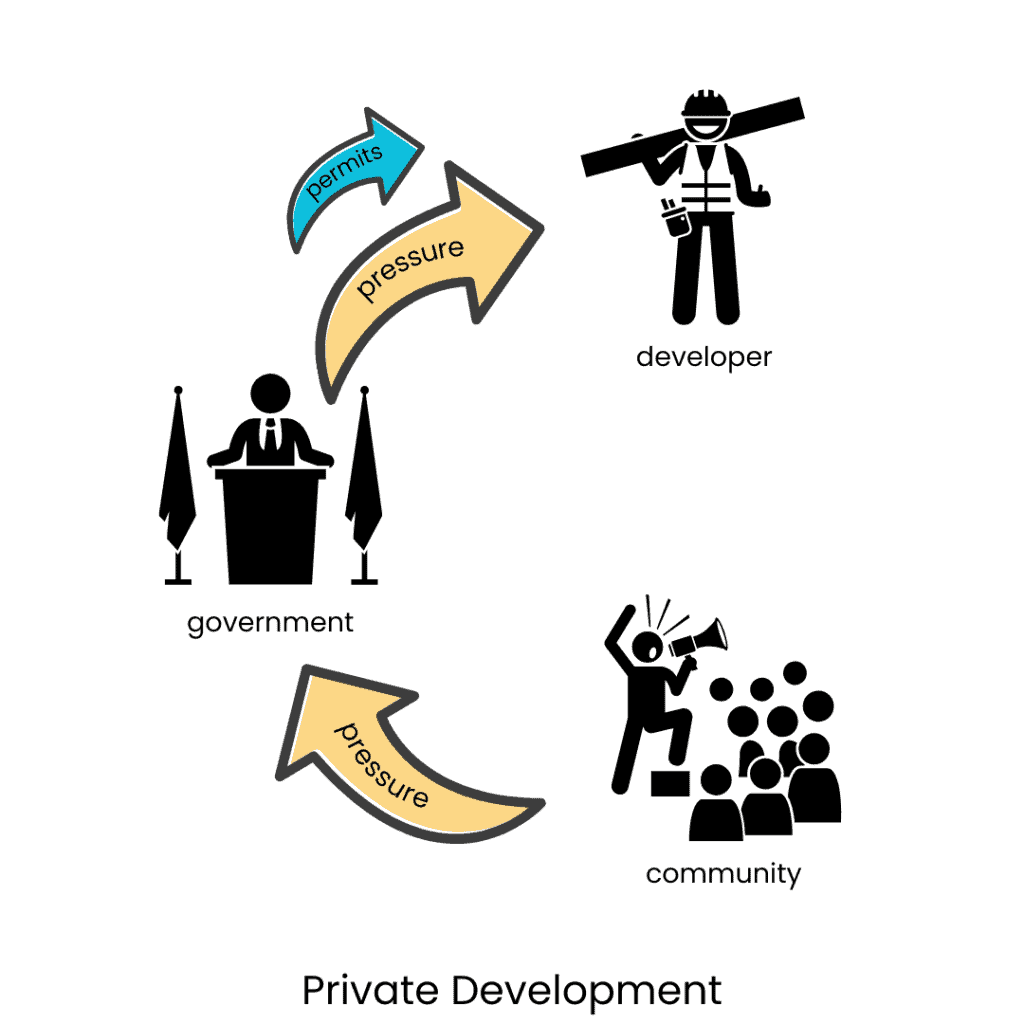

In the US, Community Benefits have historically been about negotiating between private developers and community activists, with government involvement as a kind of leverage. The Staples Centre developers, for instance, included billionaire Philip Anschutz and Rupert Murdoch, but the project also received $390 million in public subsidies and tax rebates. Rosen also considers the example of the Atlanta Falcons stadium, a controversial project built with a combination of private and public money. The definition of a CBA presented in Rosen’s book is: “a documented bargain outlining a set of programmatic and material commitments that a private developer has made to win political support from the residents of a development area and others claiming a stake in its future.”3

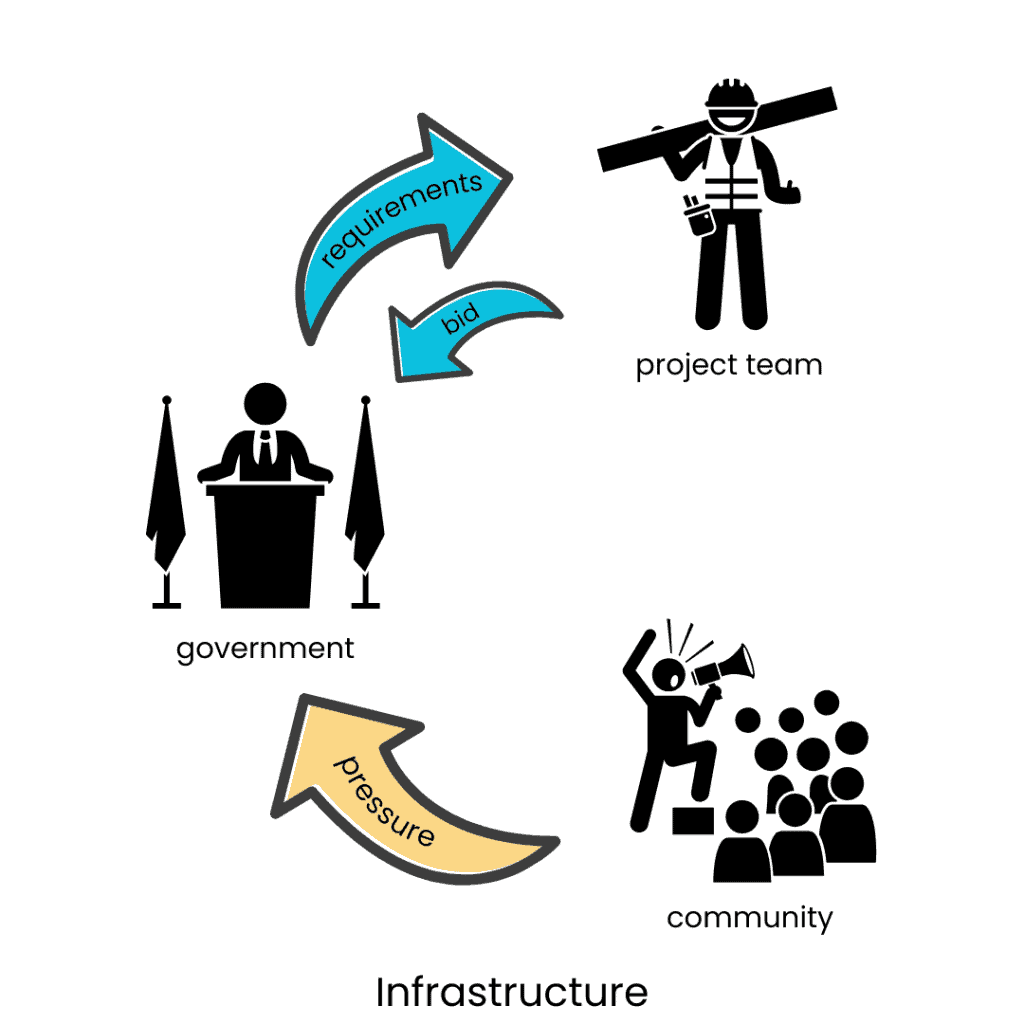

By contrast, the authors of a 2020 study of Community Benefits in the UK define CBs as “a sustainable public procurement policy that ensures that there are positive social and economic outcomes for the local community when public money is spent on goods, works and services.”4 In the UK context, though the same term is used, the focus is on public spending to maximize results for the community, rather than the tension between private development and the wellbeing of neighbourhoods.

In Canada, as is so often the case, I think we fall somewhere between the US and UK in terms of how we are developing the concept of Community Benefits. We are using CBAs modelled on American examples, but sometimes for infrastructure and transit projects that are built entirely using public money. What the 2020 study from Cardiff calls Community Benefits, we might instead call “social procurement.”

The Rexdale CBA is an agreement between Ontario Gaming GTA Limited Partnership and the City of Toronto that came about because of a community activism campaign very much on the model of American CBAs. The Gordie Howe Bridge CBA, which in some respects looks similar, has some important differences. The 2019 Community Benefits Plan document explains in its introduction:

Like the project itself, the Community Benefits Plan is the result of community members, agencies and governments coming together to identify a vision of the future. The Community Benefits Plan is uniquely ambitious, is intended to set a new benchmark for major infrastructure projects and demonstrates that the team behind the Gordie Howe International Bridge project is committed to being a good neighbour. It also guarantees that the people located most directly adjacent to the Gordie Howe International Bridge project will be among its truest beneficiaries.5

The idea behind CBAs for entertainment complexes such as the Staples Centre, the Atlanta Falcons stadium, and Casino Woodbine in Rexdale, is to mitigate harms done to marginalized neighbourhoods which might not otherwise see any benefit from a facility built in their midst for the use of tourists. With an infrastructure project like the Gordie Howe Bridge, built through a public-private partnership, there is an expectation that residents on both sides will benefit to some degree from the bridge itself; after all, they are able to travel across it. However, the project provides an opportunity to amplify those benefits, to increase “positive social and economic outcomes for the local community” from the spending of public money on infrastructure.

The city of Vancouver has a Community Benefit Agreements Policy which requires mandatory CBAs for developments over 45,000 square metres. This is government as leverage, requiring private developers to go to the table with community groups in order to receive planning permission. In the GTHA, Metrolinx has a Community Benefits and Supports Program which came about through the work of the Toronto Community Benefits Network. Metrolinx is an agency of the Ontario government, and the genesis of their Community Benefits program was a plan meant to “help take provincial dollars that were going into transit infrastructure and create jobs to ensure that communities … would further benefit from building of the Light Rail Transit.”6 This is a policy meant to take transit construction which should be of benefit to local residents anyway, and see it completed in ways that add value for the community.

From an Ontario perspective, this definition of CBAs from a 2015 article by Andrew Galley seems like an apt summary: “Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs) are a strategic tool used in the process of building community wealth. CBAs are negotiated agreements between a private or public development agent and a coalition of community-based groups. … Together, they give a voice to people in infrastructure planning and land development processes – especially those individuals who have been historically excluded or marginalized from these processes and decisions that affect them.”7 For a full picture of how CBAs are working in Canada, we have to consider both private development and public infrastructure.

My simplified diagrams of how the process works in each case:

Notes:

1. I usually lead with “I write romance novels,” because it’s simpler.

2. Rosen, Jovanna. 2023. Community Benefits. University of Pennsylvania Press. https://www.perlego.com/book/3516056.

3. Quoting Wolf-Powers, L. (2010). “Community benefits agreements and local government: A review of recent evidence.” Journal of the American Planning Association, 76(2), 141–159. DOI: 10.1080/01944360903490923.

4. Wontner, Karen Lorraine, Walker, Helen , Harris, Irina and Lynch, Jane 2020. “Maximising ‘community benefits’ in public procurement: tensions and trade-offs.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 40 (12) , pp. 1909-1939. 10.1108/IJOPM-05-2019-0395 https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/134035/3/IJOPM_Community_benefits_2nd%2Brevision_postPrint.pdf

5. https://drive.google.com/file/d/10MKzFQ4Mvv0zo9rJIBNF82OxRf03hfG5/view?usp=sharing

6. https://www.metrolinx.com/en/discover/giving-back-metrolinx-community-benefits-and-supports-program-

Recent Comments